Point reflection

In geometry, a point reflection or inversion in a point (or inversion through a point, or central inversion) is a type of isometry of Euclidean space. An object that is invariant under a point reflection is said to possess point symmetry; if it is invariant under point reflection through its center, it is said to possess central symmetry or to be centrally symmetric.

Contents |

Terminology

The term "reflection" is loose, and considered by some an abuse of language, with "inversion" preferred; however, "point reflection" is widely used. Such maps are involutions, meaning that they have order 2 – they are their own inverse: doing them twice yields the identity map – which is also true of other maps called "reflections". More narrowly, a "reflection" refers to a reflection in a hyperplane ( dimensional affine subspace – a point on the line, a line in the plane, a plane in 3-space), with the hyperplane being fixed, but more broadly "reflection" is applied to any involution of Euclidean space, and the fixed set (an affine space of dimension k, where

dimensional affine subspace – a point on the line, a line in the plane, a plane in 3-space), with the hyperplane being fixed, but more broadly "reflection" is applied to any involution of Euclidean space, and the fixed set (an affine space of dimension k, where  ) is called the "mirror". In dimension 1 these coincide, as a point is a hyperplane in the line.

) is called the "mirror". In dimension 1 these coincide, as a point is a hyperplane in the line.

In terms of linear algebra, assuming the origin is fixed, involutions are exactly the diagonalizable maps with all eigenvalues either 1 or −1. Reflection in a hyperplane has a single −1 eigenvalue (and multiplicity  on the 1 eigenvalue), while point reflection has only the −1 eigenvalue (with multiplicity n).

on the 1 eigenvalue), while point reflection has only the −1 eigenvalue (with multiplicity n).

The term "inversion" should not be confused with inversive geometry, where "inversion" is defined with respect to a circle

Examples

In two dimensions, a point reflection is the same as a rotation of 180 degrees. In three dimensions, a point reflection can be described as a 180-degree rotation composed with reflection across a plane perpendicular to the axis of rotation. In dimension n, point reflections are orientation-preserving if n is even, and orientation-reversing if n is odd.

Of the Platonic solids, all but the tetrahedron are centrally symmetric.

Formula

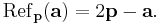

Given a vector a in the Euclidean space Rn, the formula for the reflection of a across the point p is

In the case where p is the origin, point reflection is simply the negation of the vector a (see reflection through the origin).

In Euclidean geometry, the inversion of a point X in respect to a point P is a point X* such that P is the midpoint of the line segment with endpoints X and X*. In other words, the vector from X to P is the same as the vector from P to X*.

The formula for the inversion in P is

- x*=2a−x

where a, x and x* are the position vectors of P, X and X* respectively.

This mapping is an isometric involutive affine transformation which has exactly one fixed point, which is P.

Point reflection group

The composition of two point reflections is a translation. Specifically, point reflection at p followed by point reflection at q is translation by the vector 2(q – p).

The set consisting of all point reflections and translations is Lie subgroup of the Euclidean group. It is a semidirect product of Rn with a cyclic group of order 2, the latter acting on Rn by negation. It is precisely the subgroup of the Euclidean group that fixes the line at infinity pointwise.

In the case n = 1, the point reflection group is the full isometry group of the line.

Point reflections in mathematics

- Point reflection across the center of a sphere yields the antipodal map.

- A symmetric space is a Riemannian manifold with an isometric reflection across each point. Symmetric spaces play an important role in the study of Lie groups and Riemannian geometry.

Properties

In even-dimensional Euclidean space, say 2N-dimensional space, the inversion in a point P is equivalent to N rotations over angles π in each plane of an arbitrary set of N mutually orthogonal planes intersecting at P. These rotations are mutually commutative. Therefore inversion in a point in even-dimensional space is an orientation-preserving isometry or direct isometry.

In odd-dimensional Euclidean space, say (2N + 1)-dimensional space, it is equivalent to N rotations over π in each plane of an arbitrary set of N mutually orthogonal planes intersecting at P, combined with the reflection in the 2N-dimensional subspace spanned by these rotation planes. Therefore it reverses rather than preserves orientation, it is an indirect isometry.

Geometrically in 3D it amounts to rotation about an axis through P by an angle of 180°, combined with reflection in the plane through P which is perpendicular to the axis; the result does not depend on the orientation (in the other sense) of the axis. Notations for the type of operation, or the type of group it generates, are  , Ci, S2, and 1×. The group type is one of the three symmetry group types in 3D without any pure rotational symmetry, see cyclic symmetries with n=1.

, Ci, S2, and 1×. The group type is one of the three symmetry group types in 3D without any pure rotational symmetry, see cyclic symmetries with n=1.

The following point groups in three dimensions contain inversion:

- Cnh and Dnh for even n

- S2n and Dnd for odd n

- Th, Oh, and Ih

Closely related to inverse in a point is reflection in respect to a plane, which can be thought of as a "inversion in a plane".

Inversion with respect to the origin

Inversion with respect to the origin corresponds to additive inversion of the position vector, and also to scalar multiplication by −1. The operation commutes with every other linear transformation, but not with translation: it is in the central of the general linear group. "Inversion" without indicating "in a point", "in a line" or "in a plane", means this inversion; in physics 3-dimensional reflection through the origin is also called a parity transformation.

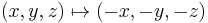

In mathematics, reflection through the origin refers to the point reflection of Euclidean space Rn across the origin of the Cartesian coordinate system. Reflection through the origin is an orthogonal transformation corresponding to scalar multiplication by  , and can also be written as

, and can also be written as  , where

, where  is the identity matrix. In three dimensions, this sends

is the identity matrix. In three dimensions, this sends  , and so forth.

, and so forth.

Representations

As a scalar matrix, it is represented in every basis by a matrix with  on the diagonal, and, together with the identity, is the center of the orthogonal group

on the diagonal, and, together with the identity, is the center of the orthogonal group  .

.

It is a product of n orthogonal reflections (reflection through the axes of any orthogonal basis); note that orthogonal reflections commute.

In 2 dimensions, it is in fact rotation by 180 degrees, and in dimension  , it is rotation by 180 degrees in n orthogonal planes;[note 1] note again that rotations in orthogonal planes commute.

, it is rotation by 180 degrees in n orthogonal planes;[note 1] note again that rotations in orthogonal planes commute.

Properties

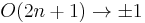

It has determinant  (from the representation by a matrix or as a product of reflections). Thus it is orientation-preserving in even dimension, thus an element of the special orthogonal group SO(2n), and it is orientation-reversing in odd dimension, thus not an element of SO(2n+1) and instead providing a splitting of the map

(from the representation by a matrix or as a product of reflections). Thus it is orientation-preserving in even dimension, thus an element of the special orthogonal group SO(2n), and it is orientation-reversing in odd dimension, thus not an element of SO(2n+1) and instead providing a splitting of the map  , showing that

, showing that  as an internal direct product.

as an internal direct product.

- Together with the identity, it forms the center of the orthogonal group.

- It preserves every quadratic form, meaning

, and thus is an element of every indefinite orthogonal group as well.

, and thus is an element of every indefinite orthogonal group as well. - It equals the identity if and only if the characteristic is 2.

- It is the longest element of the Coxeter group of signed permutations.

Analogously, it is a longest element of the orthogonal group, with respect to the generating set of reflections: elements of the orthogonal group all have length at most n with respect to the generating set of reflections,[note 2] and reflection through the origin has length n, though it is not unique in this: other maximal combinations of rotations (and possibly reflections) also have maximal length.

Geometry

In SO(2r), reflection through the origin is the farthest point from the identity element with respect to the usual metric. In O(2r+1), reflection through the origin is not in SO(2r+1) (it is in the non-identity component), and there is no natural sense in which it is a "farther point" than any other point in the non-identity component, but it does provide a base point in the other component.

Clifford algebras, Spin groups, and Pin groups

It should not be confused with the element  in the Spin group. This is particularly confusing for even Spin groups, as

in the Spin group. This is particularly confusing for even Spin groups, as  , and thus in

, and thus in  there is both

there is both  and 2 lifts of

and 2 lifts of  .

.

Reflection through the identity extends to an automorphism of a Clifford algebra, called the main involution or grade involution.

Reflection through the identity lifts to a pseudoscalar.

See also

- Affine involution

- Circle inversion

- Clifford algebra

- Congruence (geometry)

- Euclidean group

- Orthogonal group

- Parity (physics)

- Reflection (mathematics)

- Riemannian symmetric space

- Spin group

Notes

- ^ "Orthogonal planes" meaning all elements are orthogonal and the planes intersect at 0 only, not that they intersect in a line and have dihedral angle 90°.

- ^ This follows by classifying orthogonal transforms as direct sums of rotations and reflections, which follows from the spectral theorem, for instance.